What better place than at Good Old Times to get yourself some Japanese tattoos in Berlin? With passion and experience we are committed to offering the highest quality Japanese tattoos in the city.

The Japanese art of tattooing has its roots in the Japan of ancient times. Sit back, make yourself comfortable and get ready to enjoy this trip.

Genesis

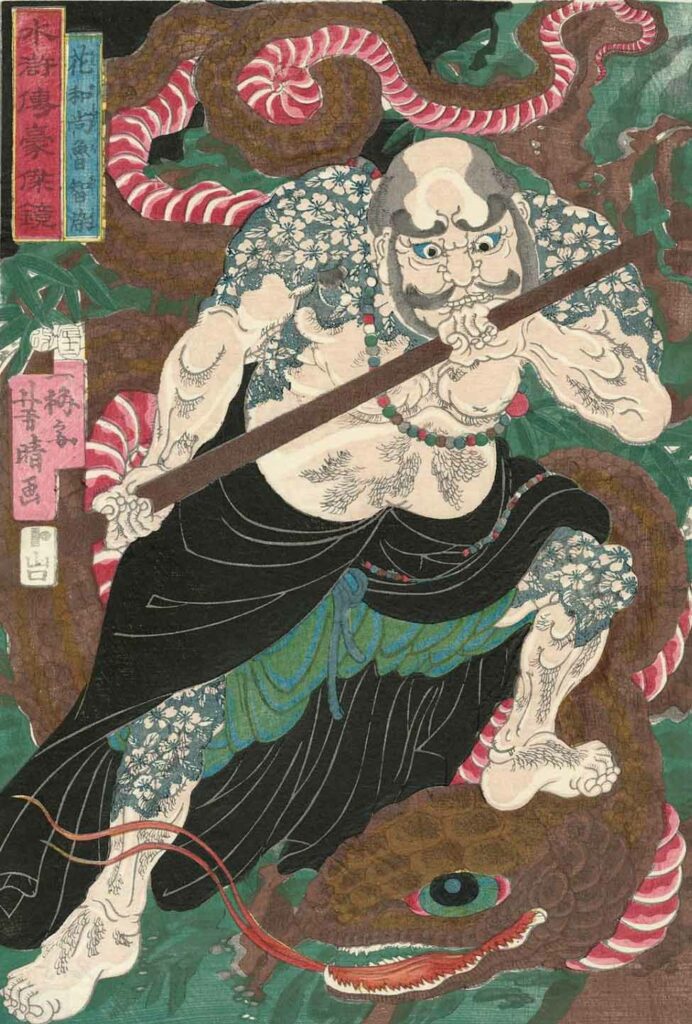

The Edo period (1603-1868) is when the image of what we now consider the “Japanese tattoo” was born. In fact, only from about the mid-19th century did tattoo designs become more detailed. During this period the woodcuts and compositions were carefully studied. Motifs from the Kabuki Theatre, Japanese folklore and Ukiyo-e became increasingly popular. The tattooing profession also experienced important developments during this time. Which led to a further refinement and improvement of the technique.

This striving for better quality and knowledge transformed the initially simple Irezumi tattoos into the majestic Horimono. A style that sees the body as a whole and adapts the tattoos to the body as a holistic concept. Japanese tattoos in Berlin, as we know them here at Good Old Times, are strongly based on this concept. Each Japanese tattoo is part of a whole body concept, which allows to give our clients an overall aesthetic picture. Multiple tattoos that blend into one big whole and create a unique work of art rather than a patchwork of small random tattoos.

The path is the goal

As you might have heard, still today in the Land of the Rising Sun tattoos are frowned upon. This is mainly because during the Edo period the Tokugawa bakufu (military government) was extremely conservative. It based its philosophical ideas on Chinese Confucian philosophy. As such regarded tattooing as a particularly severe form of punishment.

Thus, there were from time to time crackdowns on activities the government deemed undesirable. Such as tattooing, kabuki dramas, woodblock prints and various types of popular literature. Individuals that had a connection with these genres and activities developed what would come to be known as “the floating world”, Japan’s entertainment and pleasure districts. It was in this “floating world” that Edo tattooing grew and flourished.

Irebokuro

Despite the negative connotations and restrictions put in place by the Tokugawa bakufu there were many individuals who still practiced the art of tattooing, either for rebellion or as a way to define their character.

For example, visitors to the entertainment districts also got tattoos as a sign of love, the so-called Irebokuro (vow marks). They began as simple tattooed dots but escalated to names tattooed onto the inner arm.

Handkerchief clenched between her teeth, the courtesan turns away from the shimmering needle hovering above her inner arm. Her loose wisps of hair, handkerchief and disheveled kimono suggest that one moment of passion led to another: the application of a vow mark. The hand wielding the needle likely belongs to the courtesan’s lover or client, declaring the couple’s love, whether purchased or true, by tattooing his name upon her arm.

Development of the Irezumi

Tattooing in Japan kept its negative connotations until the Edo period in the early 17th century where, following the development of woodblock printing, tattooing became more of a decorative art form. This decorative style of tattooing became known as “Irezumi” 刺青 which means “to insert ink”.

Demand for decorative tattoos reached its peak with the publication of the woodblock print book Suikoden, an incredibly popular Chinese novel. Suikoden is a tale of rebel courage and manly bravery, illustrated with lavish woodblock prints showing men in heroic scenes, their bodies decorated with dragons and other mythical beasts, flowers, ferocious tigers and religious images. The novel was an immediate success, creating a demand for the type of tattoos seen in the woodblock illustrations. Due to it being a classic of the Chinese literature, the Tokugawa bakufu did not feel it was necessary to censor it.

Demand was so high that woodblock makers would instead become tattooist often using the same techniques as they would with the wood, such as using chisels and gouges. They would even use the same ink, known as Sumi. This special ink turned into greenish- blue hue when inserted into the skin and is now a distinct feature of traditional Irezumi.

Tattoo ink

The colors in the Japanese tattoo world were not very numerous.

Red was the pigment we most often find in old tattoos. Among the shades of red, the favorite for tattoos was Bengara. A darker red that tends towards brown. This, however, contained iron sulphate, which was very painful for the tattooed person due to its toxicity. another common ink was Shu, which was inorganic in origin and contained mercury.

Modern colors only came to Japan after the Second World War, with the exchange with western tattooists, and thus a larger color palette.

Irezumi kei

During the Edo period, Irezumi kei (tattoo punishment) was a criminal penalty. The crime determined the location of the tattoo. Thieves got tattoos on the arm, murderers on the head. The shape of the tattoo was based on where the crime occurred. This is how Japanese society began to associate tattoos with criminals.

At the beginning of the Meiji period, the Japanese government outlawed tattoos, which reinforced the stigma against people with tattoos and tattooing in modern-day Japan.

Japanese tattoos under censorship

Limited by a number of censorships, tattoos were a silent form of protest and resistance. People saw it as one of the few art forms and opportunities to express themselves freely.

Many works by craftsmen and artists from the Ukiyo-e Era were under censorship. A good job was a living calling card and gave the Horishi, the term for a tattoo artist, great prestige. In addition to the Bakuto, the ancestors of the Yakuza, the customer base also included all people of the lower classes. These included craftsmen, sedan chair carriers and rickshaw drivers, the so-called Bettos and the Hikeshi, the firefighters. The tattooed Otokodate are also indispensable in the cityscape of that time.

To complete the finished tattoo, it was customary to leave a signature on the client. However, Japan banned tattooing in 1872 and thus became illegal. As a result, tattoo artists stopped signing their Horimono to avoid going to jail. Also in 1889 it was forbidden for the Bettos to walk around naked. Large-scale Japanese tattoos such as bodsuits, backpieces and sleeves gradually disappeared from the cityscape and went underground. Perhaps from this time comes the “tradition” of not publicly displaying the large-scale Japanese tattoos. They were later always put on in such a way that normal clothing could hide them.

Here at Good Old Times Tattoo, we continue this tradition and find that Japanese tattoos in Berlin are most aesthetic when they adorn the wearer with powerful patterns. Motifs which, if given the need, can easily be covered depending on the occasion.

Hitokire

Perseverance was the key to being able to get a tattoo. The completion was a long, painful and also very expensive process. That didn’t stop people, often from the poorer classes, from getting tattoos. Hitokire 「⼀切」was a standard measure of payment for tattoos and was calculated in about 3 square centimeters of skin. 1 session usually lasted about two hours and cost from 4 to 6 hitokire. A whole back, called Kame no Ko 「⻲の古」, which includes part of the thigh, cost about 300 hitokire. Comparable to 50 sen (yen cents) in the 19th century until 1954. This was the daily wage of a carpenter.

Modernization

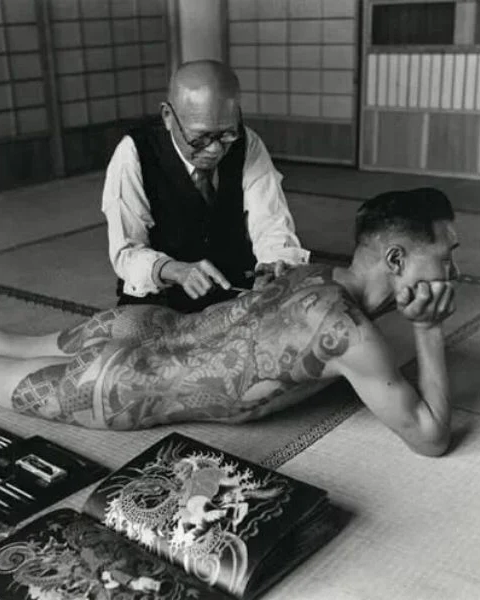

The techniques that have evolved over the years have remained essentially unchanged to this day. After the first rough attempts, the Tsuki Hari technique「突き針」, also called Imotsuki 「芋突き」, developed, whereby the needles are stuck vertically into the skin.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Hanebari 「はね針」 was born, in which the needles penetrate the skin at an angle of about 45 degrees, a technique that allows the depth of the needles to be controlled so that well reaches the dermis.

Aside from the modernization of traditional tattooing tools, the arrival of western coil machines after World War II transformed Japanese tattooing. Many tattoo artists use since then coil machines for the outlines. For the Bokashi 「ボカシ」, i.e. the filling of the areas, the traditional methods were still in vogue.

Unlike the tools, which were more or less the same for everyone, the colors were a master’s secret. Horihide (Kazuo Oguri), for example, diluted sumi with white liquor instead of water to keep the ink as sterile as to make possible.

East meets West

At Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin, in order to obtain a tattoo that is as classic as possible, Swen mostly focuses on classic Ukiyo-e motifs and art before Japan’s exchange with the western world.

Even if he is not Japanese and therefore automatically brings a Western touch to the tattoo, his Japanese tattoos in Berlin are something special. His large-scale projects that hug the body and form a unity are powerful, clear to read and understand. This mixture of traditional Japan and modern Western culture gives the wearer of his Japanese tattoos a special aesthetic that you won’t find again so quickly on the streets of Berlin.

Below you find the gallery showcasing finished Japanese tattoos in Berlin by our artist Swen Losinsky.

If we piqued your interest in Japanese tattoo style fill out our contact form to arrange a consultation appointment with Swen at Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin.

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin

Swen Losinsky at

Good Old Times Tattoo Berlin